Like most burrow-nesting petrels, White-chinned Petrels are largely nocturnal at their colonies. However, their large size gives them a degree of bravado when it comes to dealing with Brown Skuas, and they occasionally sit outside their burrow entrances during the day

The White-chinned Petrel Procellaria aequinoctialis is the largest member of the petrel family after the two giant petrels Macronectes spp. It breeds at sub-Antarctic islands, with three regional populations: the nominate subspecies breeds at South Georgia and locally on the Falklands in the south-west Atlantic Ocean, and at the Prince Edward, Crozet and Kerguelen Islands in the south-west Indian Ocean, whereas P. a. steadi breeds at islands south of New Zealand.

Peter Ryan scans for seabirds, including White-chinned Petrels, on a Southern Ocean voyage

White-chinned Petrels are the seabird most often caught on longlines in the Southern Ocean. Since I started checking the age and sex of hooked seabirds returned to South African ports by fishery observers, I have examined nearly 4000 White-chinned Petrels. They are competent divers, occasionally reaching depths of up to 16 m, which allows them to retrieve baited hooks for some distance behind vessels. Indeed, they are thought to facilitate the bycatch of albatrosses by bringing hooks to the surface, only to be displaced by larger albatrosses.

The White-chinned Petrel is the largest burrow-nesting petrel, and their burrows tend to be fairly obvious; most have an entrance moat

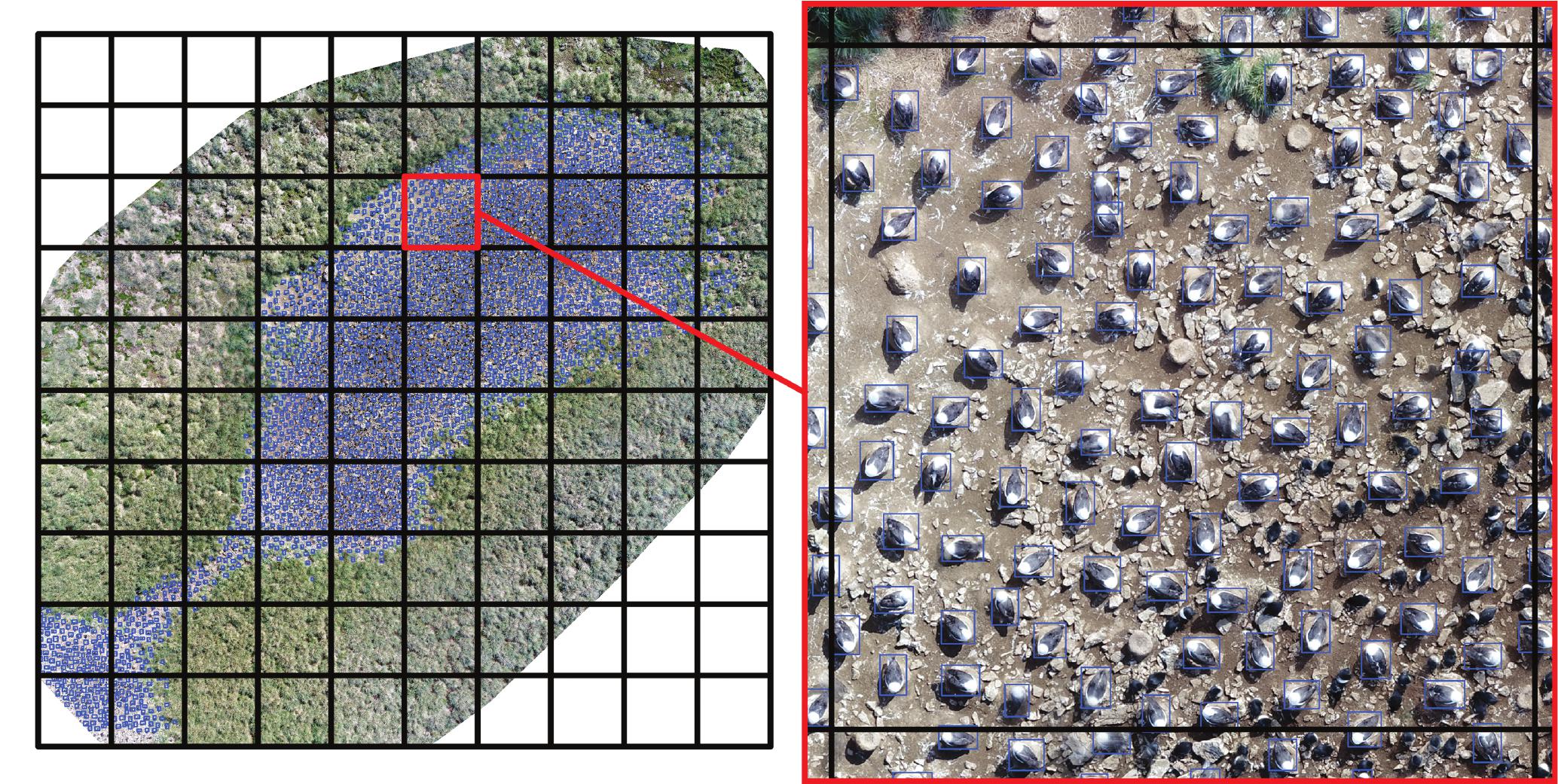

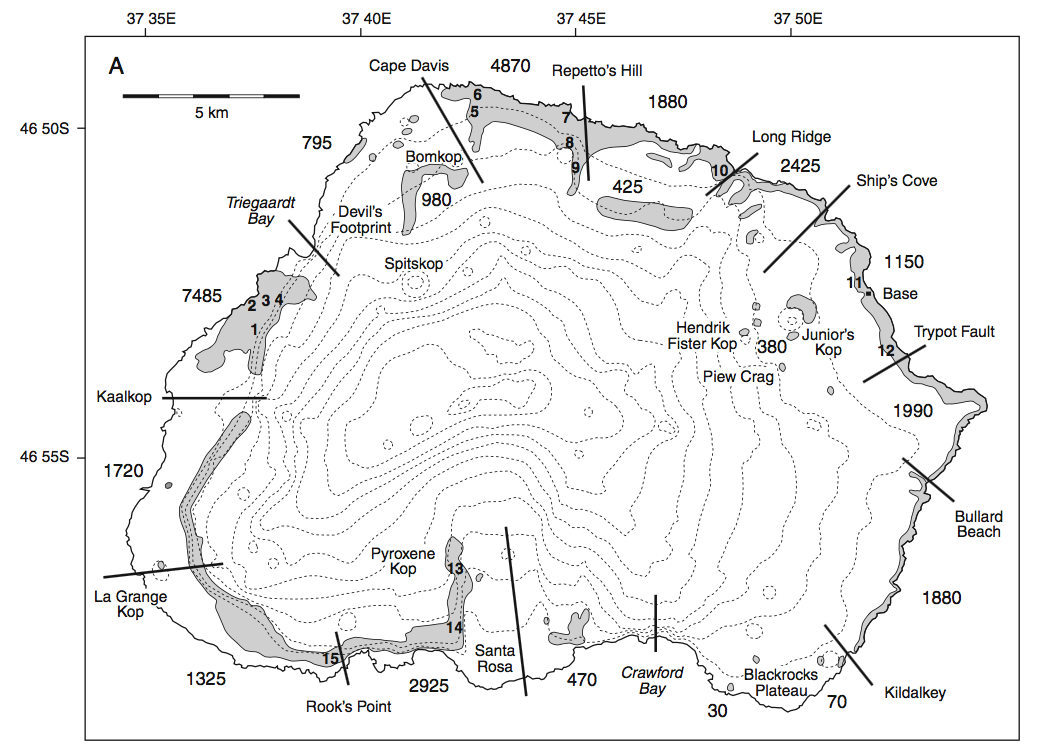

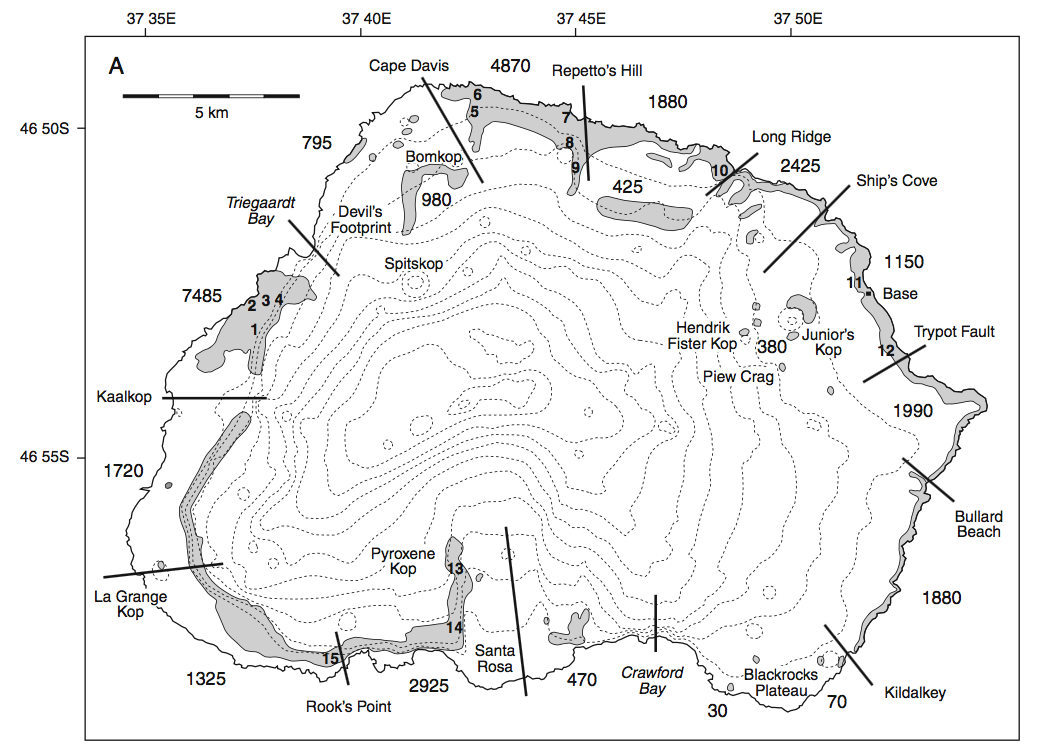

The large, distinctive burrow nests of White-chinned Petrels make it possible to attempt a complete survey of their breeding distribution on Marion Island. Most colonies are close to the coast, but nests occur up to 420 m above sea level below Spitskop (map from Ryan et al. 2012). They favour well-drained sites with deep soils for burrowing, avoiding more recent black lava flows

Given concerns about their population status – the species is listed a Vulnerable globally – it was the first burrowing petrel for which we attempted to estimate the breeding population at the Prince Edward Islands. Genevieve Jones, Ben Dilley and I conducted a systematic survey of all burrows in April 2009, and Ben followed up with occupancy checks the following breeding season. This indicated a total population of some 30 000 pairs on Marion Island and at least another 10 000 pairs on Prince Edward Island. Subsequent randomized transects conducted around Marion Island in 2015 by Ben, Stefan Schoombie, Alexis Osborne and I indicated that this initial estimate was too low, with an extrapolated 40 000 pairs breeding on the island. This makes the Prince Edward Islands the third most important breeding site for the nominate subspecies after South Georgia and Kerguelen.

In March and April at Marion Island, White-chinned Petrel chicks exercise their wings outside their burrows at night in preparation for fledging. A few fail to make it back to the safety of their burrows by day break, and typically fall prey to Brown Skuas

Despite their frequent mortality on long-lines, White-chinned Petrel numbers have shown the greatest recovery among burrow-nesting petrels on Marion Island following the eradication of cats in 1991. Their breeding success is generally quite high (average 59% of attempts fledge a chick), suggesting that their chicks are seldom attacked by the introduced House Mice. In this regard, they are probably helped by their large size and by breeding in summer, when mice have a greater range of other food options than in winter. Surprisingly, large chicks may occasionally be killed by Grey Petrels if they find a White-chinned Petrel chick in their burrow when they return to breed in autumn.

A White-chinned Petrel glides by the photographer in the Southern Ocean

At sea, White-chinned Petrels are among the most vocal of petrels, often giving their characteristic chittering call during squabbles over food

All photographs by Peter Ryan

References:

Dilley, B.J., Davies, D., Schoombie, S., Schoombie, J. & Ryan, P.G. 2019. Burrow wars and sinister behaviour among burrow-nesting petrels at sub-Antarctic Marion Island. Ardea 107: 97-102.

Dilley, B.J., Hedding, D.W., Henry, D.A.W., Rexer-Huber, K, Parker, G.C., Schoombie, S., Osborne, A. & Ryan, P.G. 2019. Clustered or dispersed: testing the effect of sampling strategy to census burrow-nesting petrels with varied distributions at sub-Antarctic Marion Island. Antarctic Science 31: 231-242.

Dilley, B.J., Schoombie, S., Stevens, K., Davies, D., Perold, V., Osborne, A., Schoombie, J., Brink, C.W., Carpenter-Kling, T. & Ryan, P.G. 2018. Mouse predation affects breeding success of burrow-nesting petrels at sub-Antarctic Marion Island. Antarctic Science 30: 93-104.

Dilley, B.J., Schramm, M. & Ryan, P.G. 2016. Modest increases in densities of burrow-nesting petrels following the removal of cats (Felis catus) from Marion Island. Polar Biology 40: 625-637.

Rollinson, D.P., Dilley, B.J. & Ryan, P.G. 2014. Diving behaviour of white-chinned petrels and its relevance for mitigating longline bycatch. Polar Biology 37: 1301-1308.

Ryan, P.G. 2001. Partial leucism in Whitechinned Petrels. Bird Numbers 10(2): 6-7.

Ryan, P.G., Dilley, B.J. & Jones, M.G.W. 2012. The distribution and abundance of White-chinned Petrels (Procellaria aequinoctialis) breeding at the sub-Antarctic Prince Edward Islands. Polar Biology 35: 1851-1859.

Peter Ryan, FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, University of Cape Town, 29 April 2022

NOTE: First published on the Mouse-Free Marion website on 26 April 2022.

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español