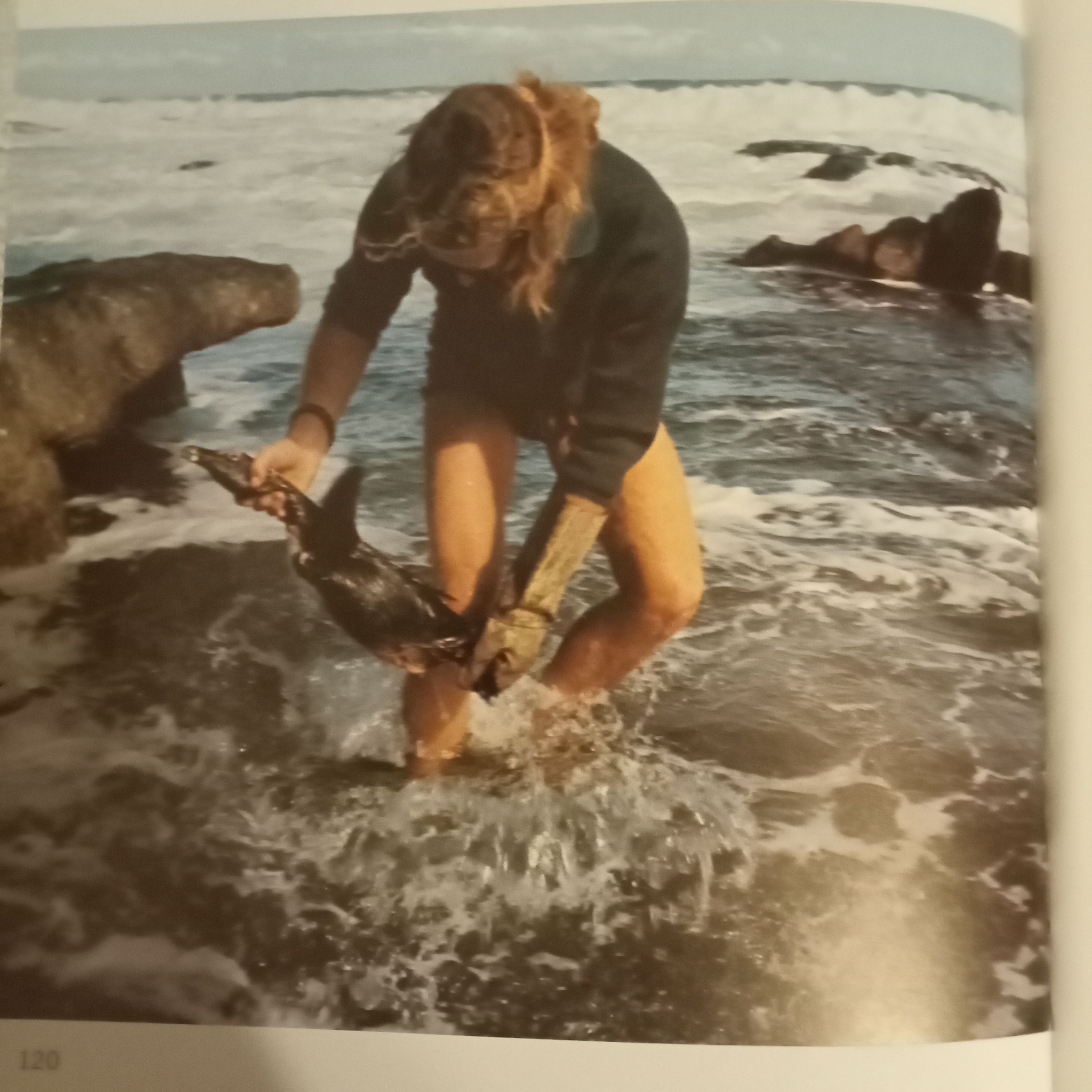

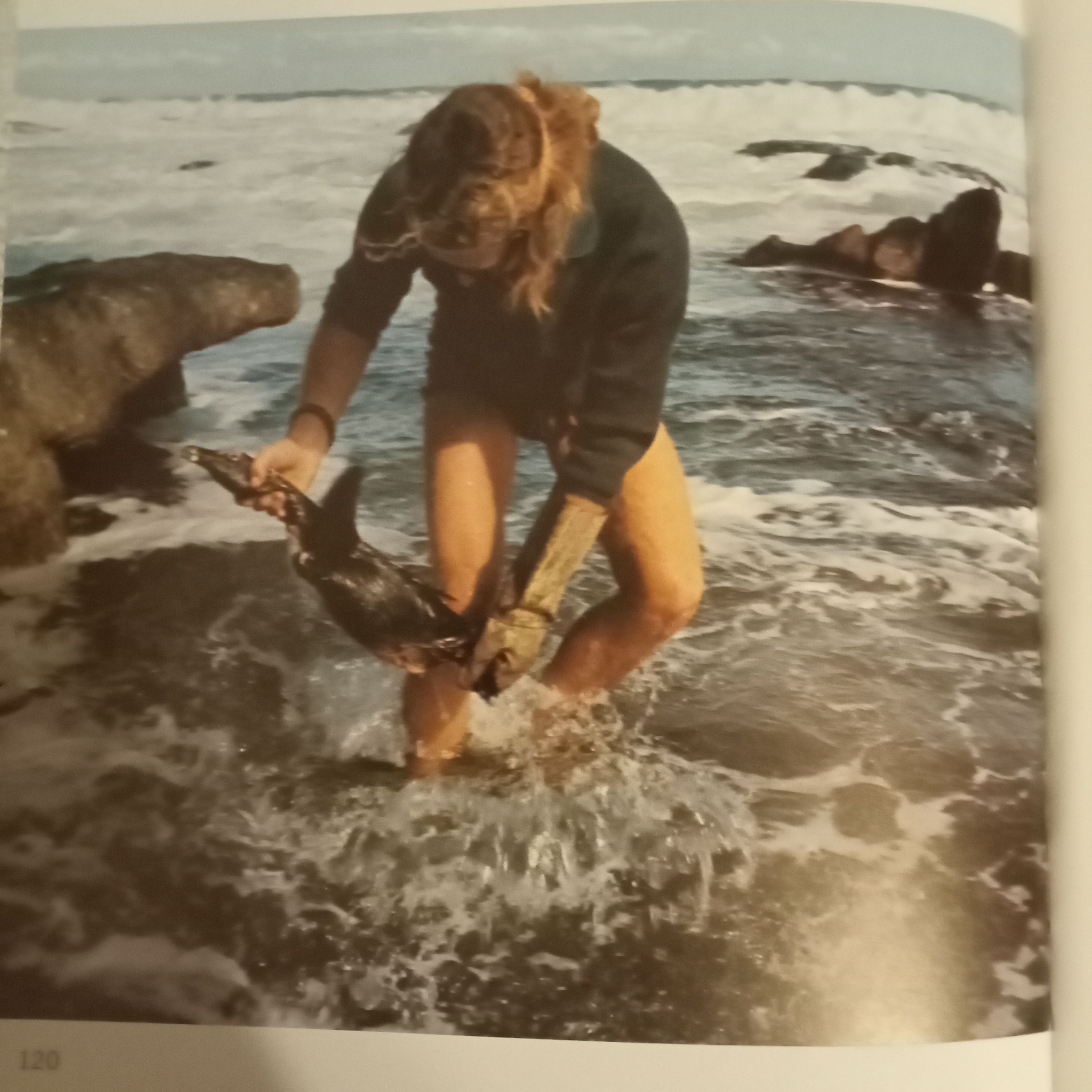

Catching an oiled African Penguin in the surf on Dassen Island in 1971/72. From Holmes, M. 1976. Cry of the Jackass, Johannesburg: High Keartland Publications.

Note: This is the third in a new series entitled ACAP Monthly Missives. Click here to read a description of the series and to access previous missives by title. January’s Monthly Missive is set to be the first by an invited guest. Please do look out for it.

**********************************

I moved countries from a land-locked Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) to Cape Town, South Africa in December 1970 at the age of 23. Within a month I was living full time on Dassen Island up the west coast within sight (on a clear day) from the top of Table Mountain. I stayed there with very few breaks for the next 18 months, studying the breeding biology of African Penguins Spheniscus demersus, then at serious risk from oil spills on behalf of the SANCCOB Foundation. The Endangered penguin is now sadly even more at risk due to a shortage of its anchovy and pilchard prey due to overfishing, and the crowded breeding flats I knew are now practically deserted.

As well as penguins and other breeding seabirds, Dassen also supported a large population of long-introduced European Rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus (still present) and numbers of feral cats Felis catus. The rabbits usefully enhanced my otherwise sparse diet, but I observed that the cats were feeding on penguin and cormorant chicks and also killing migratory Palaearctic terns at a summer night roost. My efforts at cat control likely made little difference to their numbers, but it was my first introduction to the harm an introduced mammalian predator can cause on a seabird island. The cats were eventually eradicated years later as I reported in a 2013 publication. Following my island sojourn I joined the FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology at the University of Cape Town in 1973, continuing to study seabirds, with research visits to nearly all of southern Africa’s coastal islands, including those that now form part of Namibia. A suite of publications written with colleagues ensued in the 1970s and 1980s, reviewing the history, presence and effects of alien mammals (and sometimes other taxa) on island life.

On Marion Island after a day’s field work in the early 1980s, with Valdon Smith (left) and Marthan Bester (right)

With sub-Antarctic islands and their rich birdlife beckoning, in 1978 I visited South Africa’s Marion Island in the southern Indian Ocean. Gough Island in the South Atlantic followed soon after. Initially I managed seabird research, concentrating on albatrosses and petrels. Although not directly involved with the long but ultimately successful campaign to remove Marion’s feral cats, I did serve on an advisory committee so was able to keep track of its progress, and I also studied the improved breeding success of several species of burrowing petrels post cat. With the cats gone by 1991, thoughts turned to the remaining introduced mammal, the House Mouse.Mus musculus. A colleague, Stephen Chown, and I organized a two-day workshop in 1995 to assess the impact of Marion’s mice and consider the desirability of their eradication. “Side trips” to write up the history of introduced mammals and birds on Marion followed, as did a successful effort to eradicate introduced trout, then present in a single stream.

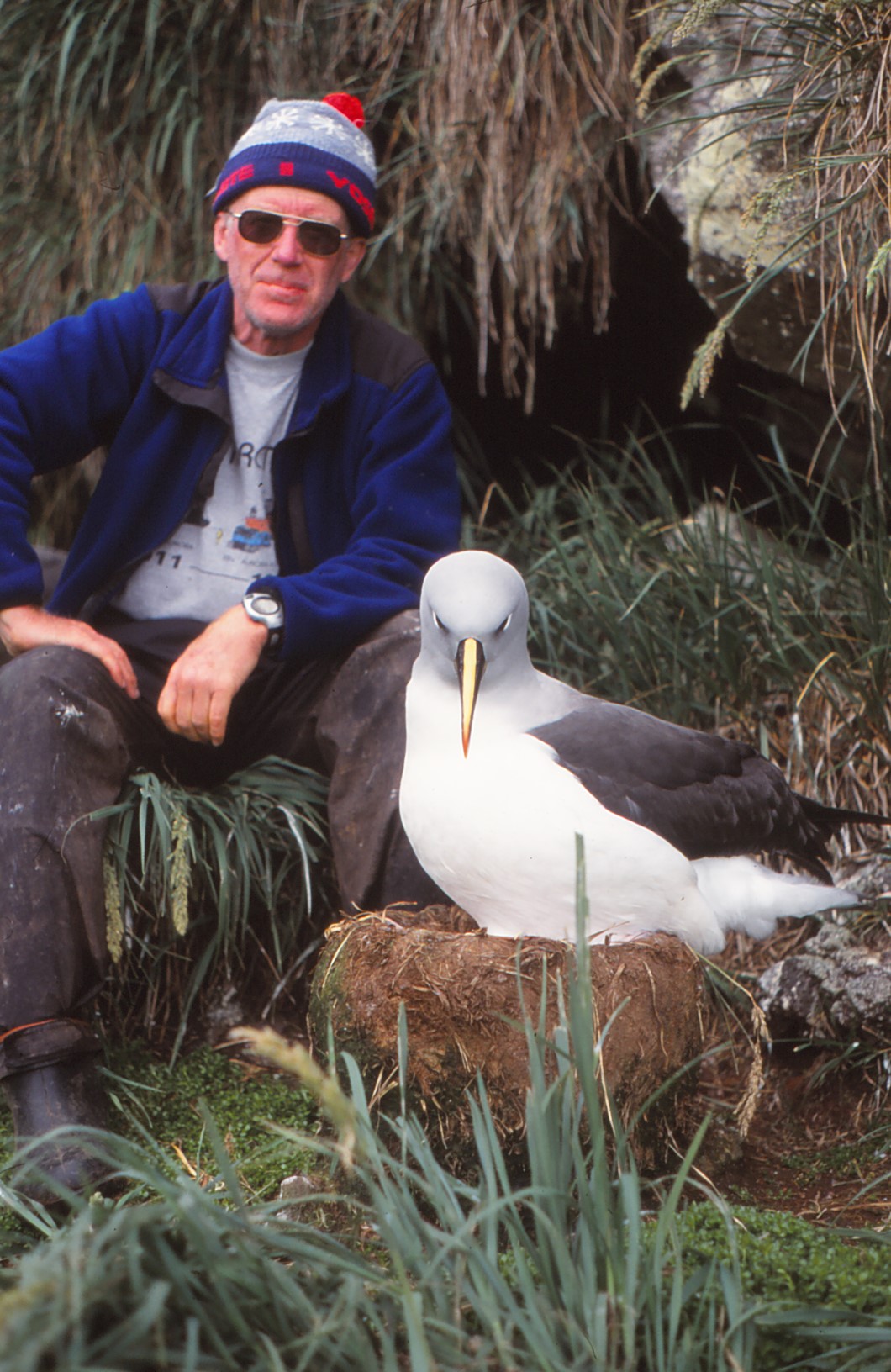

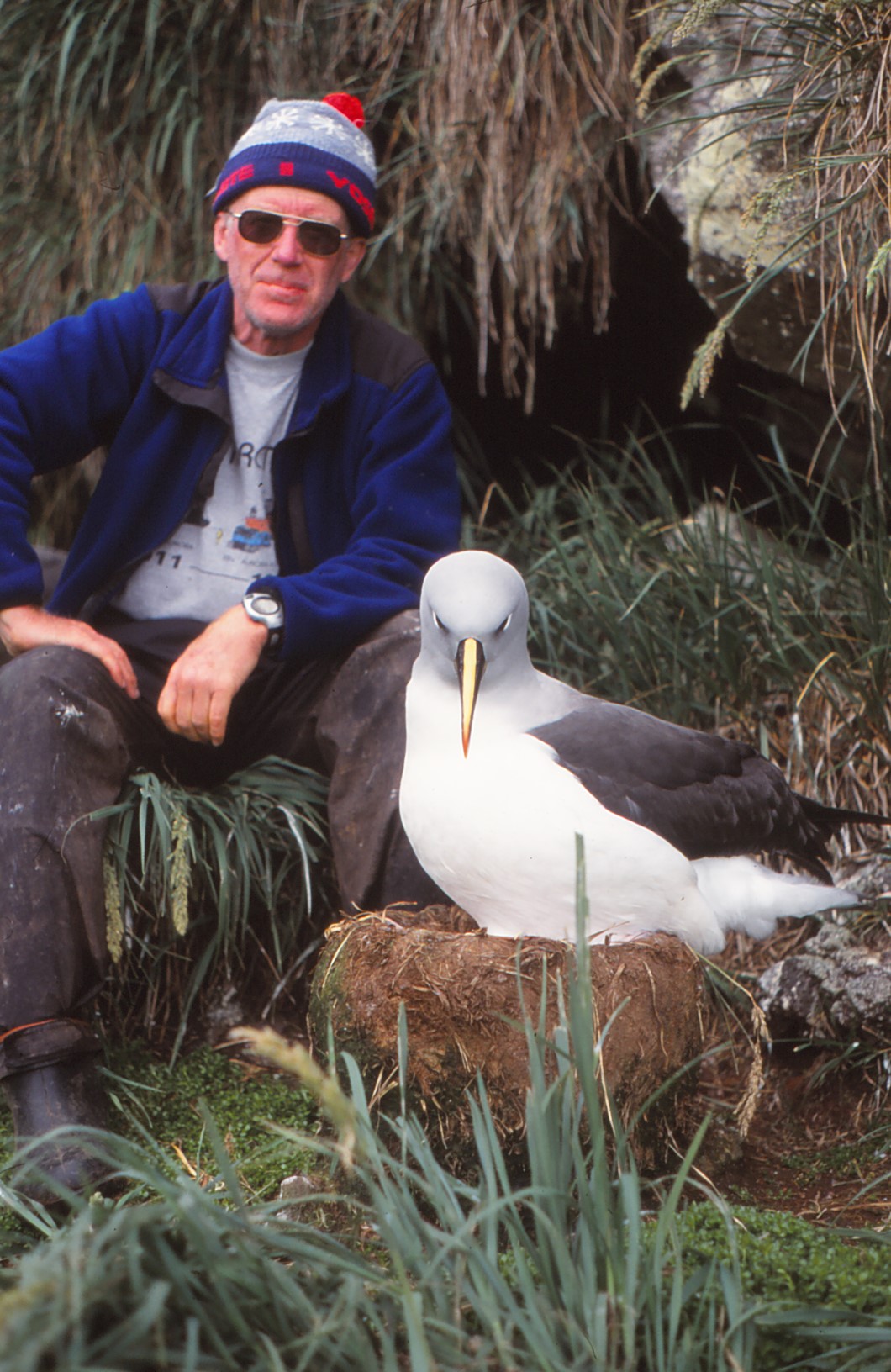

Uncharacteristically clean shaven and sunburnt in 2001 (but still with the same Yosemite beanie). Next to an Endangered Grey-headed Albatross Thalassarche chrysostoma prior to it being banded while camping on introduced mammal-free Prince Edward Island, photograph by Bruce Dyer

In 1994 I travelled to Australia and New Zealand on sabbatical, when I made short visits to three sub-Antarctic islands studying environmental practices. On New Zealand’s then rat-infested Campbell Island (now thankfully rodent free) I noted the cordon sanitaire of rodent traps around the landing stage and base buildings; on Enderby shortly after the removal of all its introduced mammals I saw the recovering vegetation still littered with cattle skulls and rabbit burrows. Then on Australia’s Macquarie I noted the effects of that island’s rabbits on the vegetation and erosion. Would be great to go back to these three islands, now all free of introduced mammals, to see how they have recovered.

I later became involved with pest eradication directly, for six years working to eradicate a recently arrived alien plant, Procumbent Pearlwort Sagina procumbens, on Gough. Sadly (and in my view incorrectly) the organization that took over from me stopped the programme, making all our hard work - that entaled dangerous work on coastal cliffs by trained climbers - come to nought. However, we did manage to remove a few other newly arrived plant species that had not spread from their points of introduction near the meteorological station.

A Vulnerable Wandering Albatross Diomedea exulans chick is ‘scalped’ by mice on Marion Island: it will not survive many nights of such attacks, photograph by Stefan Schoombie

In the first decade of the century, I helped conduct research and co-authored publications and reports on the House Mice of both Gough and Marion. On both islands they had turned to attacking seabirds, The long-term study colonies with colour-banded albatrosses and giant petrels I had set up a few decades earlier on both islands then proved their worrth as they helped quantify the damage caused by the mice. We also conducted trials related to poison baiting and the likely effects on non-target species. Sadly, the effort to eradicate Gough's mice in 2021 failed, although the island's seabirds managed to get in a good breeding season this year (click here). It is likely be some years before another attempt is made, allowing the mice to rebuild their numbers and maybe turning to attacking birds again.

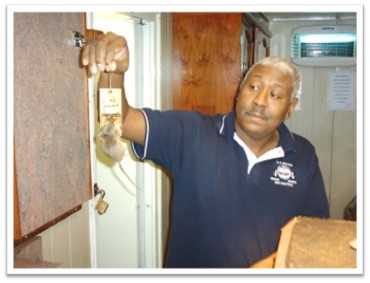

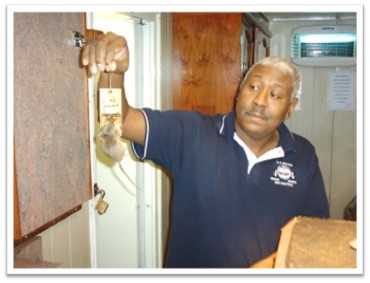

An important, and perhaps sometimes overlooked, issue is back-loading introduced pests to a visiting vessel that then travels on to a locality free of the pest. I wrote about this in 2013 after House Mice were inadvertently back-loaded to a supply ship from mouse-infested Gough Island in the South Atlantic Ocean before the vessel proceeded to land a research party on mouse-free Inaccessible Island (click here).

Caught! Chief Steward Neville Genisson with the back-loaded House Mouse caught aboard the S.A. Agulhas after departing Gough Island for mouse-free Inaccessible Island

My sub-Antarctic adventures on Gough and Marion came to an end in 2014 after a total of 49 visits – one short of a round fifty – with the South African National Antarctic Programme (SANAP). During this time, I was fortunate to have visited Marion’s neighbour, Prince Edward, on four occasions. That island has always been free of introduced mammals. The comparison in the densities and numbers of burrowing petrels, and in seed-bearing vegetation and insect life, in the absence of cats and mice was remarkable. Subsequently, I have devoted much of my time writing for the website of the Mouse-Free Marion Project, that aims to eradicate the island’s albatross-killing mice. Although I am unlikely to ever visit Marion Island again, just to know in a few years’ time it is finally free of all its introduced mammals after over two centuries, and to hear from researchers much younger than myself that the albatrosses and petrels are no longer being scalped and having to die grisly deaths will be reward enough.

Celebrating my 75th birthday in January this year with running friends who donated to the Mouse-Free Marion Project in my name (click here)

Selected Bibliography on Island Pests

Angel, A. & Cooper, J. 2006. A review of the impacts of introduced rodents on the Islands of Tristan da Cunha and Gough (South Atlantic). RSPB Research Report No. 17. Sandy: Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. 58 pp.

Angel, A. & Cooper, J. 2011. Review of the Impacts of the House Mouse Mus musculus on Sub-Antarctic Marion Island, Prince Edward Islands. Report to the Prince Edward Islands Management Committee, South African National Antarctic Programme. Rondebosch: CORE Initiatives. 57 pp.

Angel, A, Wanless, R.M. & Cooper, J. 2008. Review of impacts of the introduced House Mouse on islands in the Southern Ocean: are mice equivalent to rats? Biological Invasions 11: 1743-1754.

Caravaggi, A., Cuthbert, R.J., Ryan, P.G., Cooper, J. & Bond, A.L. 2018. The impacts of introduced House Mice on the breeding success of nesting seabirds on Gough Island. Ibis 161: 648-661.

Chown, S.L. & Cooper, J. 1995. The Impact of Feral House Mice at Sub-Antarctic Marion Island and the Desirability of Eradication: Report on a Workshop held at the University of Pretoria, 16-17 February 1995. Pretoria: Directorate: Antarctica & Islands, Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism. 18 pp.

Cooper, J. 1977. Food, breeding and coat colour of feral cats on Dassen Island. Zoologica Africana 12: 250-252.

Cooper, J. 1995. Introduced biota at the subantarctic and cool temperate islands of the Southern Ocean: the issues. In: Dingwall, P.R. (Ed.). Progress in Conservation of Subantarctic Islands. Gland: World Conservation Union. pp. 123-125.

Cooper, J. 1995. Introduced island biota: discussion and recommendations. In: Dingwall, P.R. (Ed.). Progress in Conservation of Subantarctic Islands. Gland: World Conservation Union. pp. 133-138.

Cooper, J. & Berruti, A. 1989. The conservation status of South Africa's continental and oceanic islands. In: Huntley, B.J. (Ed.). Biotic Diversity in Southern Africa: Concepts and Conservation. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. pp. 239-253.

Cooper, J. & Brooke, R.K. 1982. Past and present distribution of the feral European Rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus on southern African offshore islands. South African Journal of Wildlife Research 12: 71-75.

Cooper, J. & Brooke, R.K. 1986. Alien plants and animals on South African continental and oceanic islands: species richness, ecological impacts and management. In: MacDonald, I.A.W., Kruger, F.J. & Ferrar, A.A. (Eds). The Ecology and Management of Biological Invasions in Southern Africa. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. pp. 133-142.

Cooper, J., Crafford, J.E. & Hecht, T. 1992. Introduction and extinction of Brown Trout, Salmo trutta, in an impoverished subantarctic stream. Antarctic Science 4: 9-14.

Cooper, J., Cuthbert, R.J., Gremmen, N.J.M., Ryan, P.G. & Shaw, J.D. 2011. Earth, fire and water: applying novel techniques to eradicate the invasive plant, procumbent pearlwort Sagina procumbens, on Gough Island, as World Heritage Site in the South Atlantic. In: Veitch, C.R., Clout, M.N. & Towns, D.R. (Eds). Island Invasives: Eradication and Management. Gland: World Conservation Union & Auckland: Centre for Biodiversity and Biosecurity. pp. 162-165.

Cooper, J., Cuthbert, R.J. & Ryan, P.G. 2013. An overlooked biosecurity concern? Back-loading at islands supporting introduced rodents. Aliens: The Invasive Species Bulletin 33: 28-31.

Cooper, J. & Dyer, B.M. 2013. The eradication of feral cats from Dassen Island: a first for Africa? Aliens: The Invasive Species Bulletin 33: 35-37.

Cooper, J. & Fourie, A. 1991. Improved breeding success of Great-winged Petrels Pterodroma macroptera following control of feral cats Felis catus at subantarctic Marion Island. Bird Conservation International 1: 171-175.

Cooper, J., Hockey, P.A.R. & Brooke, R.K. 1985. Introduced mammals on South and South West African islands: history, effects on birds and control. In: Bunning, L.J. (Ed.). Proceedings of the Symposium on Birds and Man, Johannesburg 1983. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand Bird Club. pp. 179-203.

Cooper, J. Marais, A.V.N., Bloomer, J.P. & Bester, M.N. 1995. A success story: breeding of burrowing petrels (Procellaridae) before and after eradication of feral cats Felis catus at sub-Antarctic Marion Island. Marine Ornithology 23: 33-37.

Cooper, J., Parker, G., Rexer-Huber, K. & Ryan, P. 2011. The burrowing petrels of Gough Island are threatened by alien mice. Tristan da Cunha Newsletter 48: 28-30.

Cooper, J., Ryan, P.G. & Glass, J.P. 2006. Eradicating invasive species in the United Kingdom Overseas Territory of Tristan da Cunha. Aliens 23: 1, 3.

Cooper, J., van Wyk, J.C.P. & Matthewson, D.C. 1994. Effects of small mammal trapping on birds at sub-Antarctic Marion Island. South African Journal of Antarctic Research 24: 59.

De Villiers, M.S. & Cooper, J. 2008. Conservation and management. In: Chown, S.L. & Froneman, P.W. (Eds). The Prince Edward Islands: Land-Sea Interactions in a Changing Ecosystem. Stellenbosch: Sun PReSS. pp. 113-131.

De Villiers, M.S., Cooper, J., Carmichael, N., Glass, J.P., Liddle, G.M., McIvor, E., Micol, T. & Roberts, A. 2006. Conservation management at Southern Ocean islands: towards the development of best-practice guidelines. Polarforschung 75: 113-131.

MacDonald, I.A.W. & Cooper, J. 1995. Insular lessons for global biodiversity conservation with particular reference to alien invasions. In: Vitousek, P.M., Loope, L.L. & Adsersen, H. (Eds). Islands. Biological diversity and ecosystem function. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 189-203.

McClelland, G.T.W., Cooper, J. & Chown, S.L.2013. Evidence of breeding by diving petrels and storm petrels at Marion Island after the eradication of feral cats. Ornithological Observations 4: 90-93.

Preston, G.R., Dilley, B.J., Cooper, J.m Beaumont, J., Chauke, L.F., Chown, S.L., Devanunthan, N., Dopolo, M., Fikizolo, L., Heine, J., Henderson, S., Jacobs, C.A., Johnson, F., Kelly, J., Makhado, A.B. Marais, C., Maroga, J., Mayekiso, M., McClelland, G., Mphepya, J., Muir, F., Ngcaba, N. Ngcobo, N., Parkes, J.P., Paulsen, P., Schoombie, S., Springer, K., Stringer, C., Valentine, H.J., Wanless, R.M. & Ryan, P.G. 2019. South Africa works towards eradicating introduced house mice from sub-Antarctic Marion Island: the largest island yet attempted for mice. In: Veitch, C.R., Clout, M.N., Martin, A.R., Russell, J.C. & West, C.J. (Eds). Island invasives: scaling up to meet the challenge. Occasional Paper SSC No. 62. Gland: IUCN. pp. 40-46.

Wanless, R.M., Cooper, J., Slabber, M.J. & Ryan, P.G. 2010. Risk assessment of birds foraging terrestrially at Marion and Gough Islands to primary and secondary poisoning. Wildlife Research 37: 524-530.

Wanless, R.M., Fisher, P., Cooper, J., Parkes, J., Ryan, P.G. & Slabber, M. 2008. Bait acceptance by house mice: an island field trial. Wildlife Research 35: 806-811.

Wanless, R.M., Ryan, P.G., Altwegg, R., Angel, A., Cooper, J., Cuthbert, R.J. & Hilton, G.M. 2009. From both sides: dire demographic consequences of carnivorous mice and longlining for the Critically Endangered Tristan Albatrosses on Gough Island. Biological Conservation 142: 1710-1718.

Watkins, B.P. & Cooper, J. 1986. Introduction, present status and control of alien species at the Prince Edward Islands, sub-Antarctic. South African Journal of Antarctic Research 16: 86-94.

John Cooper, Emeritus Information Officer, Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, 06 December 2022

ACAP Secondee Maximiliano Hernandez (right) with Dragonfly's Environmental Data Scientist, Yvan Richard (left); photograph courtesy of Sarah Wilcox

ACAP Secondee Maximiliano Hernandez (right) with Dragonfly's Environmental Data Scientist, Yvan Richard (left); photograph courtesy of Sarah Wilcox A Black-browed Albatross - one of the first species, alongside the White-chinned Petrel, Maximiliano chose for his first assessments due to the abundance of population data and their high catch rates in Argentinian fisheries; photograph by Maximiliano Hernandez

A Black-browed Albatross - one of the first species, alongside the White-chinned Petrel, Maximiliano chose for his first assessments due to the abundance of population data and their high catch rates in Argentinian fisheries; photograph by Maximiliano Hernandez

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español

Salvin's Albatross; photograph by Matt Charteris & Black Petrel; photograph by Virginia Nicol

Salvin's Albatross; photograph by Matt Charteris & Black Petrel; photograph by Virginia Nicol

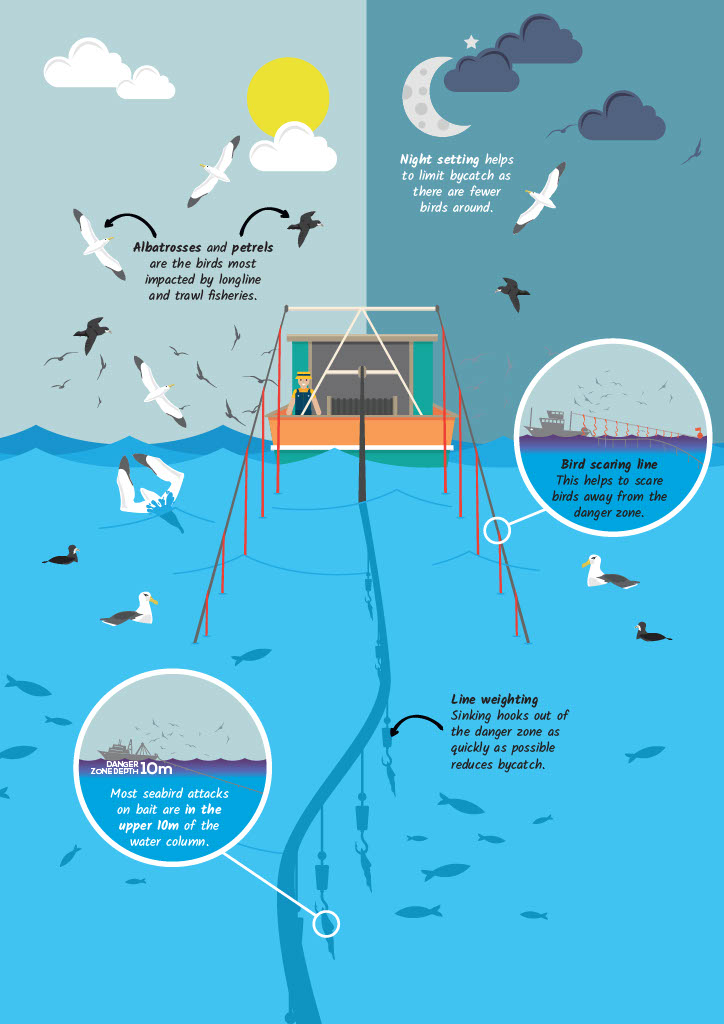

A page from ACAP's Bycatch Mitigation Fact Sheet on Pelagic Line-Weighting - available to download from ACAP's website

A page from ACAP's Bycatch Mitigation Fact Sheet on Pelagic Line-Weighting - available to download from ACAP's website