ACAP’s Executive Secretary, Marco Favero is attending meetings of the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) in Bali, Indonesia over this and next week.

Starting today with the 2nd Meeting of the Electronic Reporting and Electronic Monitoring Intersessional Working Group (EM-ER WG2) over two days, the Commission’s Scientific Committee will then meet for a week in its 12th Regular Session (WCPFC SC12).

The working group meeting is considering monitoring matters that were discussed during the Seventh Meeting of ACAP’s Seabird Bycatch Working Group (SBWG7), held earlier this year in Chile.

During the Scientific Committee session ACAP will present an information paper offering advice for reducing the impact of pelagic longline fishing operations on seabirds. The ACAP paper’s abstract follows:

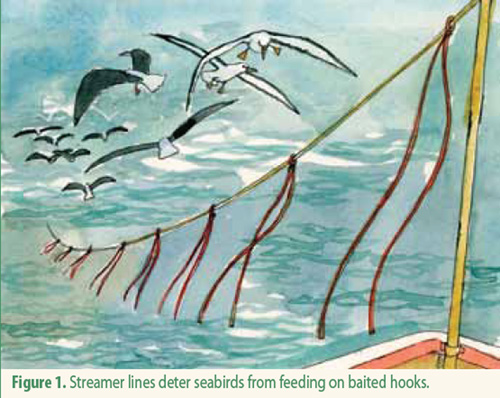

“The incidental mortality of seabirds, mostly albatrosses and petrels, in longline fisheries continues to be a serious global concern and was the major reason for the establishment of the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP). In longline fisheries seabirds are killed when they become hooked and drowned while foraging for baits on longline hooks as the gear is deployed. They also can become hooked as the gear is hauled, although many of these seabirds can be released alive with careful handling. ACAP routinely reviews the scientific literature regarding seabird bycatch mitigation in fisheries, and on the basis of these reviews updates its best practice advice. The most recent review was conducted in May 2016 at ACAP’s Seabird Bycatch Working Group and Advisory Committee meetings (ACAP 2016), and this document presents a distillation of that review for the consideration of the WCPFC Scientific Committee. A combination of weighted branch lines, bird-scaring lines and night setting remains the best practice approach to mitigate seabird bycatch in pelagic longline fisheries. Changes in this regard only applied to the recommended minimum standards for line weighting regimes, now updated to the following configurations: (a) 40 g or greater attached within 0.5 m of the hook; or (b) 60 g or greater attached within 1 m of the hook; or (c) 80 g or greater attached within 2 m of the hook. In addition, ACAP endorsed the inclusion in the list of best practice measures of two hook-shielding devices as stand-alone mitigation measures. Such hook-shielding devices encase the point and barb of baited hooks until a prescribed depth or time immersed to prevent seabird becoming hooked during line setting. The following performance requirements were used by ACAP to assess the efficacy of hook-shielding devices in reducing seabird bycatch: (a) the device shields the hook until a prescribed depth of 10 m or immersion time of 10 minutes is reached; (b) the device meets current recommended minimum standards for branch line weighting; and (c) experimental research has been undertaken to allow assessment of the effectiveness, efficiency and practicality of the technology against the ACAP best practice seabird bycatch mitigation criteria. ACAP recognizes that factors such as safety, practicality and the characteristics of the fishery should also be taken into account when considering the efficacy of seabird bycatch mitigation measures and consequently in the development of advice and guidelines on best practice.”

Other papers by New Zealand authors to be considered by the Scientific Committee will provide guidance on levels of observer coverage and report on the hook pod, described as a novel seabird mitigation option.

References:

Debski, I., Pierre, J. & Knowles, K. 2016. Observer coverage to monitor seabird captures in pelagic longline fisheries. WCPFC-SC12-2016/ EB-IP-07. 11 pp.

Favero, M., Wolfaardt, A. & Walker, N. 2016. ACAP advice for reducing the impact of pelagic longline fishing operations on seabirds. WCPFC-SC12-2016/ EB-IP-05. 11 pp.

Walker, N., Sullivan, B., Debski, I. & Knowles, K. 2016. Development and testing of a novel seabird mitigation option, the Hook Pod, in New Zealand pelagic longline fisheries. WCPFC-SC12-2016/ EB-IP-06. 11 pp

John Cooper, ACAP Information Officer, 01 August 2016

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español