Satellite-tracked juvenile Black-browed Albatross off Cape Town, South Africa; photograph by Estelle Smalberger

In April 2021, 19 satellite tags were attached to Black-browed Albatross Thalassarchre melanophris chicks prior to their departure from Bird Island in the South Atlantic by the British Antarctic Survey’s Black-browed Albatross Juvenile Tracking project. The fledged birds are being tracked in near real-time using the Argos system with maps showing that the majority then travelled to the continental shelf and close inshore waters of southern Africa. The project explains that the main aims of the tracking study are to map the birds’ distribution to determine their overlap with fisheries and the main environmental drivers of their movements, and to assess their survival rate in the critical months after fledging. The project aims to run to February 2022.

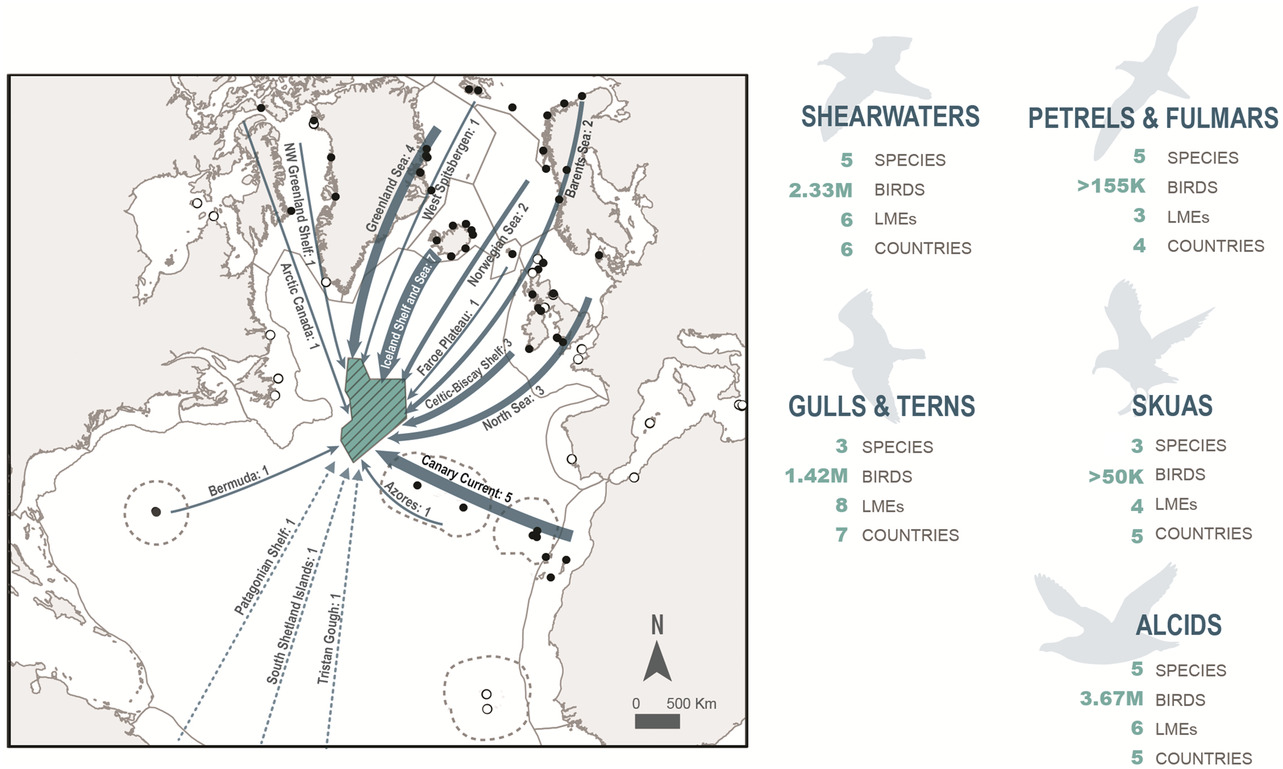

Tracks of the satellite-tagged Black-browed Albatrosses from Bird Island as at 07 August 2021

That one of these 19 birds has now been photographed at sea some three months after fledging is totally unexpected. The story follows with Trevor Hardaker of the pelagic tour company Zest for Birds reporting to the Pelagic birding in Cape Town with Zest for Birds Facebook page of photographing a juvenile Black-browed Albatross wearing a back-mounted satellite tracker off Cape Town, South Africa.

Trevor writes: “Some fantastic feedback received from James Crymble, the Zoological Field Assistant for the Black-browed Albatross Juvenile Tracking project, about the bird with the satellite tracker on it that we saw on our pelagic trip last Saturday, 31 July 2021. James says: “Astronomical odds. This has caused quite a stir here on Bird Island. Based on the info you provided (I sent him the date, time and GPS position that we recorded the bird at), the most likely candidate is Argos ID 205662. Device was deployed on 23/04/2021 with the chick fledging on 02/05/2021. Has travelled 10,474 km as of today (06 August 2021)!” Trevor continues: “How awesome is that news…?! That bird only fledged from the nest 96 days ago and it has already travelled 10 474km!! That’s an average of just over 109 km that it has travelled every single day since it left the nest!! It’s no small wonder that we all love these incredible ocean wanderers so much!”

Read more in ACAP Latest News about the project.

With thanks to Trevor Hardaker and Estelle Smalberger.

John Cooper, ACAP Information Officer, 10 August 2021

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español