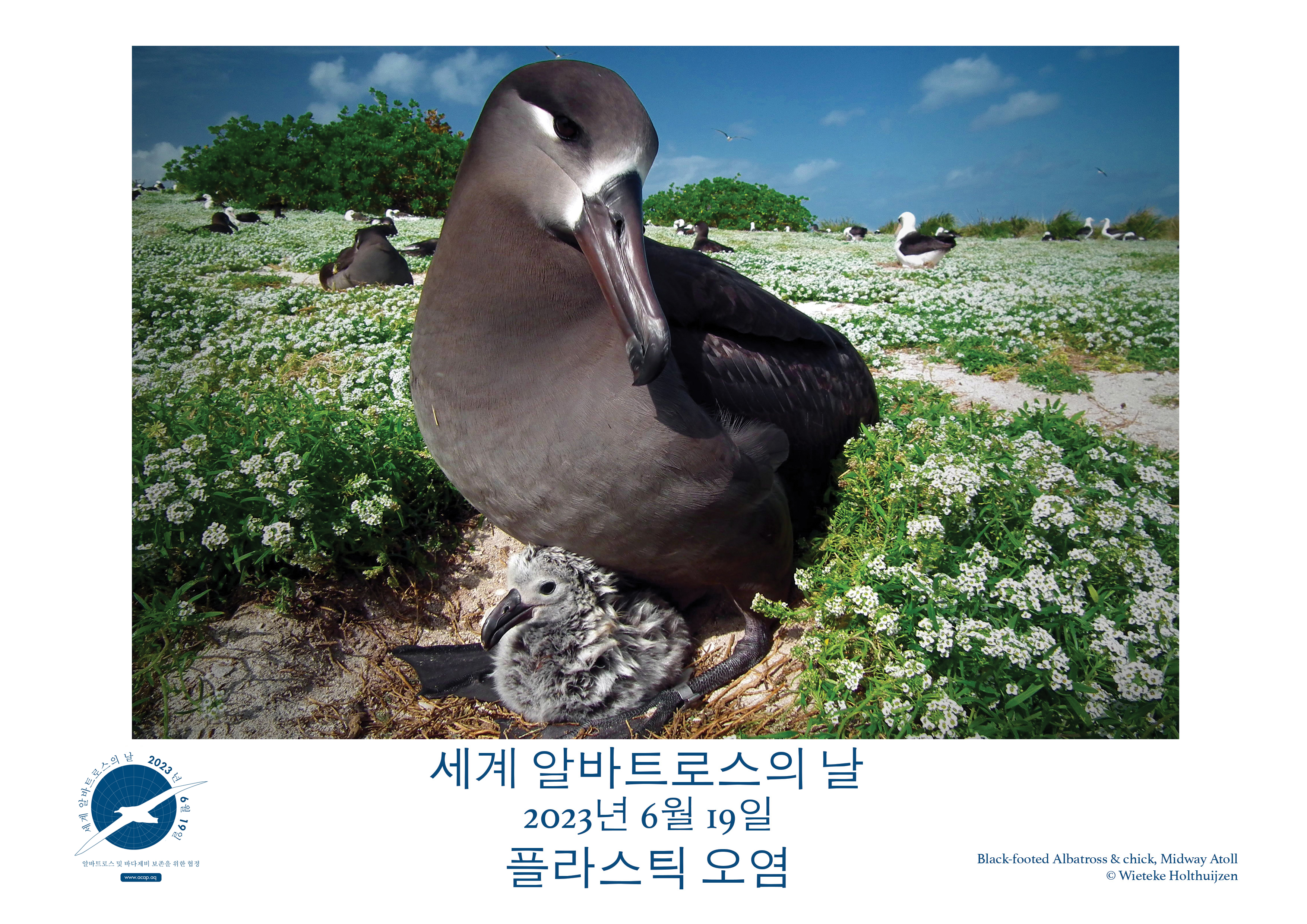

Black-footed Albatross and chick, Midway Atoll, photograph by Wieteke Holthuijsen, poster design by Bree Forrer

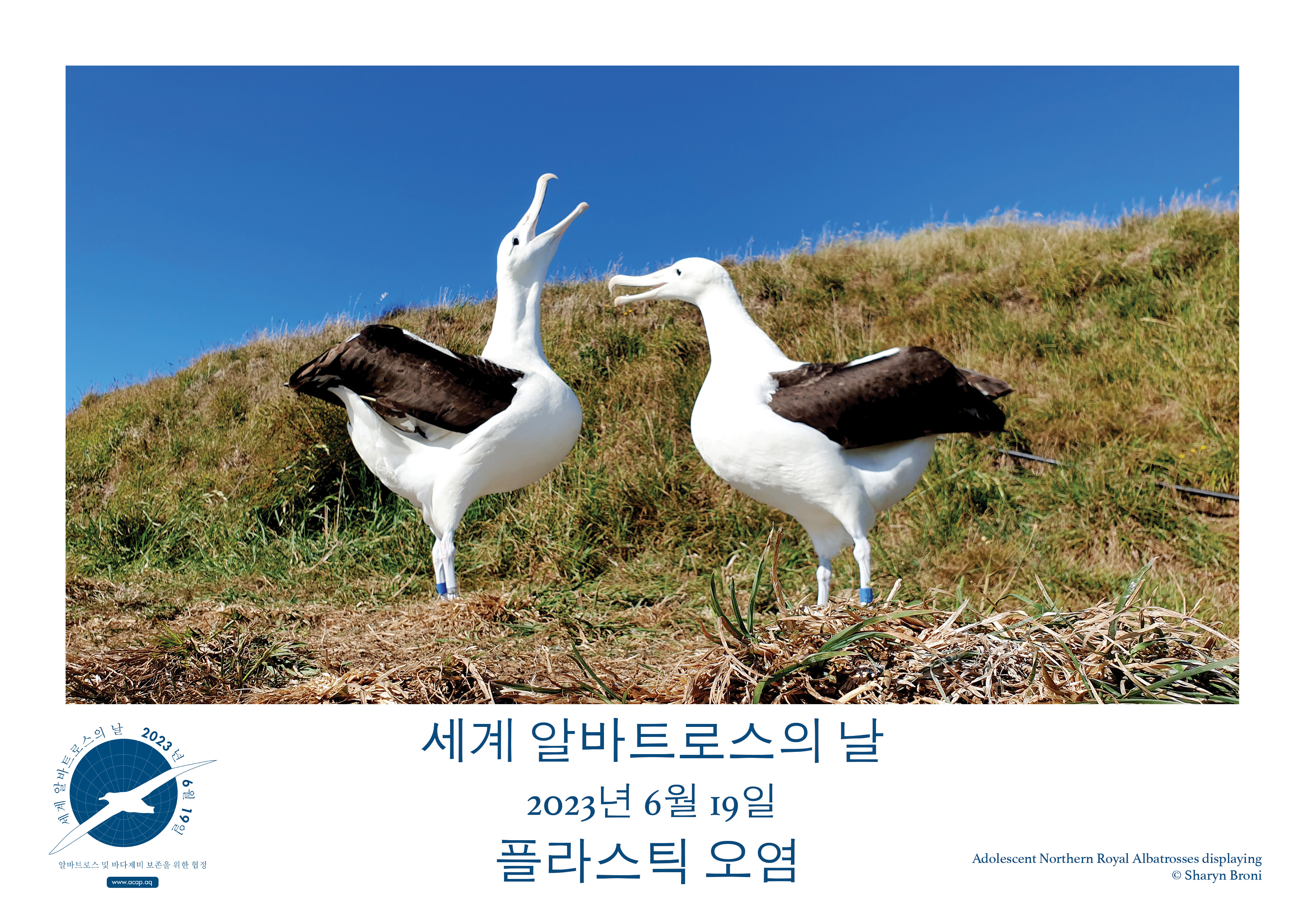

The Albatross and Petrel Agreement is pleased to release its second set of 12 freely downloadable photo posters for this year’s World Albatross Day with its theme of “Plastic Pollution” in a second Asian language following Japanese – this time in Korean (available here). Previously, the poster set has been made available in ACAP’s three official languages – English, French and Spanish, and in Portuguese. The ‘WAD2023’ logo is also available in Korean.

The Republic of Korea is not a Party to the Agreement, nor has a breeding population of an ACAP-listed species. However, it is an ACAP range state* by way of undertaking fishing that interacts with ACAP-listed species, notably through its high-seas longline fisheries for tuna in the Atlantic, Indian, Pacific and Southern Oceans.

ACAP has made its Seabird Bycatch Mitigation Fact Sheets available in Korean. A Korean version of the ACAP Seabird Bycatch ID Guide is also planned.

It is hoped the photo posters can be used within Korea to increase awareness of the conservation plight being faced by albatrosses and petrels and aid the country in celebrating World Albatross Day come 19 June.

Adolescent Northern Royal Albatrosses display at Pukekura/Taiaroa Head; photograph by Sharyn Broni, poster design by Bree Forrer

With grateful thanks for help with translations from Vivian Fu and Yuna Kim Williams, and to photographers Sharyn Broni and Wieteke Holthuijsen.

* “Range State” means any State that exercises jurisdiction over any part of the range of albatrosses or petrels, or a State, flag vessels of which are engaged outside its national jurisdictional limits in taking, or which have the potential to take, albatrosses and petrels” [from the Agreement text].

John Cooper, Emeritus Information Officer, Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, 11 May 2023

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español  The World Migratory Bird Day event campaign poster by Augusto Silva

The World Migratory Bird Day event campaign poster by Augusto Silva

A Black-footed Albatross chick sits near a decoy bird on Mexico's Guadalupe Island; photo courtesy of Pacific Rim Conservation. According to the research, active restoration programmes targeting albatrosses, petrels and shearwaters which involve the use of social attraction or a combination of social attraction and translocation are seeing positive outcomes from the interventions.

A Black-footed Albatross chick sits near a decoy bird on Mexico's Guadalupe Island; photo courtesy of Pacific Rim Conservation. According to the research, active restoration programmes targeting albatrosses, petrels and shearwaters which involve the use of social attraction or a combination of social attraction and translocation are seeing positive outcomes from the interventions. The focus of the study; a Cory's Shearwater grounded by lights; photograph by Beneharo Rodríguez

The focus of the study; a Cory's Shearwater grounded by lights; photograph by Beneharo Rodríguez