Amsterdam Island from the air, photograph by Thierry Micol

Célia Lesage (Terres Australes et Antarctiques Françaises, Saint-Pierre, France) and colleagues have published in the journal Polar Biology on a seabird survey conducted on France’s sub-Antarctic Amsterdam Island over 2021/22, prior to the 2024 eradication effort directed at alien rodents. The island’s three breeding albatrosses were included in the survey with counts of occupied nests (Amsterdam Diomedea amsterdamensis 65 pairs, Sooty Phoebetria fusca 515 pairs, Indian Yellow-nosed Thalassarche carteri 29 671 pairs.)

The paper’s abstract follows:

“An invasive predator eradication campaign is planned for 2024 on Amsterdam Island, one of world’s top priority island for seabird conservation. In order to monitor the effects on seabird colonies post-eradication, a survey of burrow-nesting species and population monitoring of albatrosses, penguins, skuas and terns was organised pre-eradication. Several counting techniques and acoustic methods were used to infer presence/absence of burrow-nesting species and to estimate abundance of other species, as well as genetic methods for species identification. In total 14 breeding (or probably breeding) seabird species were detected on Amsterdam Island, among which eight burrowing petrels including two species never described on the island: the Juan Fernandez petrel Pterodroma externa and the sooty sherwater Ardenna grisea. Based on these new data, the introduced mammal eradication campaign on Amsterdam, if successful, will likely be extremely beneficial for seabird conservation, and may also favor the colonization of Amsterdam by new seabird species.”

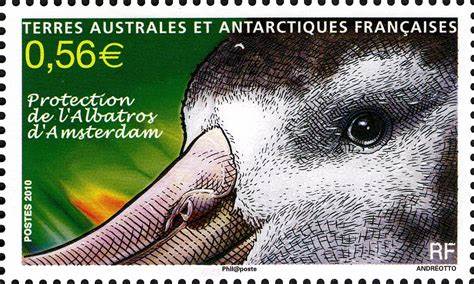

Amsterdam Albatross – endemic to Amsterdam Island

Read about the completed eradication here.

Reference:

Lesage, C., Cherel, Y., Delord, K., D’orchymont, Q., Fretin, M., Levy, M., Welch, A. & Barbraud, C. 2024. Pre-eradication updated seabird survey including new records on Amsterdam Island, southern Indian Ocean. Polar Biology 47: 1093–1105. {PDF here]

03 October 2024

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español  ACAP Executive Secretary Dr Christine Bogle meets with students visiting Projeto Albatroz's newly opened Marine Environmental Education and Visitation Centre in the coastal city of Cabo Frio

ACAP Executive Secretary Dr Christine Bogle meets with students visiting Projeto Albatroz's newly opened Marine Environmental Education and Visitation Centre in the coastal city of Cabo Frio A translocated Laysan Albatross egg gets a new owner, photograph by Hob Osterlund

A translocated Laysan Albatross egg gets a new owner, photograph by Hob Osterlund

The problem: this Wandering Albatross chick has been attacked by Marion Island's introduced House Mice, photograph by Lucy Smyth, 22 May 2022, Read more at what is to be done at

The problem: this Wandering Albatross chick has been attacked by Marion Island's introduced House Mice, photograph by Lucy Smyth, 22 May 2022, Read more at what is to be done at