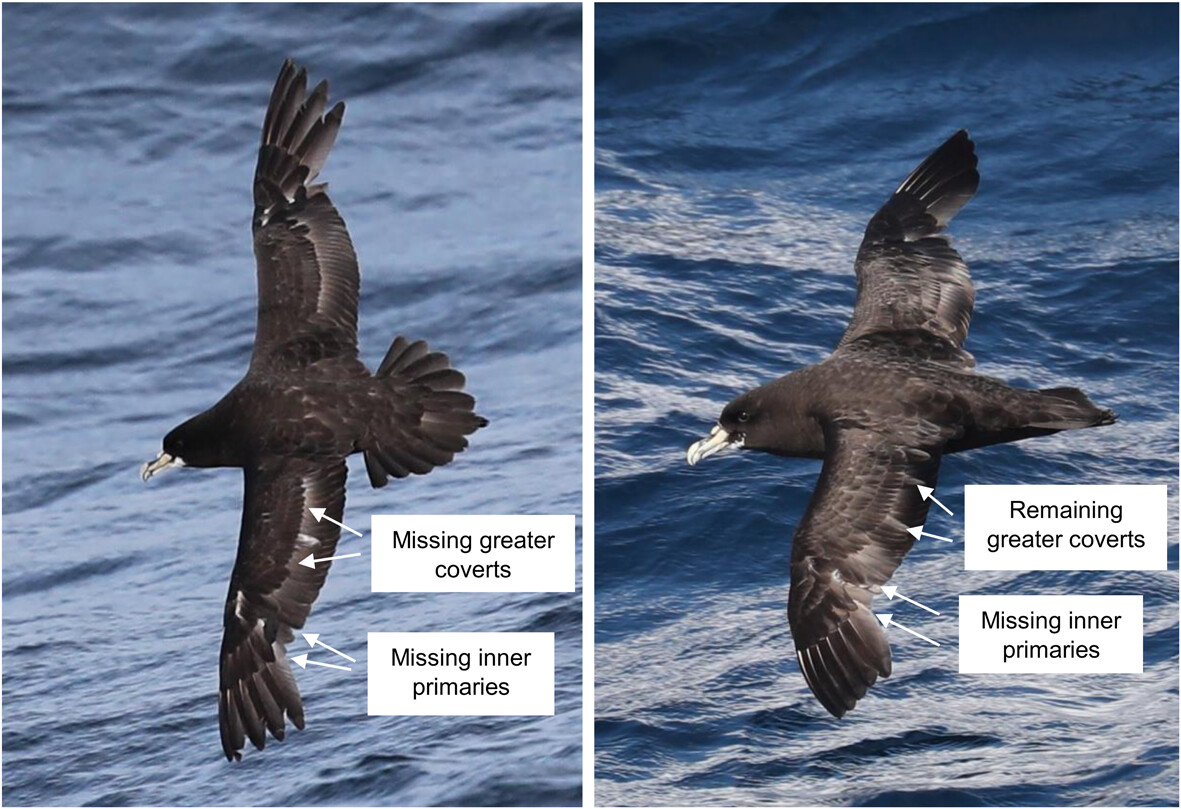

White-chinned Petrels moulting 4–5 inner primaries at the start of primary moult also replace most of their greater secondary coverts before the start of secondary moult, photographs by Peter Ryan (from the publication)

Oluwadunsin Adekola and Peter Ryan (FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, University of Cape Town, South Africa) have published open access in the Journal of Avian Biology on flight feather moult in 2431 White-chinned Petrels Procellaria aequinoctialis killed by fisheries off South Africa.

The paper’s abstract follows:

“The cost of moult is substantial, and the timing and intensity of flight feather moult can influence survival and fitness, especially in large, long-winged species such as many seabirds. We explore variation in wing and tail moult in > 2400 white-chinned petrels Procellaria aequinoctialis killed in fisheries off southern Africa to assess how they integrate moult into their annual cycle and whether wing moult impacts their behaviour at sea. All petrels showed a simple descendent primary moult and one active moult centre, although moult of P2–3 sometimes started before P1. The Underhill–Zucchini moult model estimated that adult primary moult started after breeding on 7 May (± 8 days SD) and lasted 103 days (mean end date 20 August ± 10 days). Adult males started and finished moult 10 days before females. Immature petrels started primary moult earlier than adults, and their moult was probably more protracted as they moulted fewer primaries at once (1.9 ± 1.2) when compared to adults (2.3 ± 1.1), independent of sex. Adult moult was particularly intense in the inner primaries, growing up to six feathers at once, slowing to at most 3–4 outer primaries. The secondary moult started two weeks after the primary moult, once 3–4 primaries had been dropped. Secondary moult typically started with the innermost secondaries, plus inward waves from S1 and S5 in 2.7 ± 1.3 active moult centres (range 1–6), replacing 4.6 ± 2.7 (1–13) secondaries at once. Adults had more intense secondary moult (4.7 ± 2.8 growing feathers) than immatures (3.6 ± 2.3), with no difference between the sexes. However, photographs of non-moulting birds at sea show that 27% of birds do not replace all secondaries each year. The tail moult usually commenced at the start of the secondary moult and was highly variable, with 1–12 rectrices growing at once. Adults had more active centres (3.0 ± 1.4) than immatures (2.3 ± 1.0). Moult symmetry was greater among the primaries (84%) than either the secondaries (46%) or rectrices (68%). Although adult wing moult was intense, there was no marked reduction in flight activity among breeding adults fitted with leg-mounted activity loggers during the moult period. Our findings are largely in accord with previous studies of moult in petrels, but our large sample size reveals considerable variation among individuals, which is surprising given the high cost of moult. Future studies should attempt to investigate the factors determining this variation.”

Reference:

OAdekola, O.E. & Ryan, P.G. 2025. Variation in wing and tail moult intensity in white-chinned petrels. Journal of Avian Biology doi.org/10.1111/jav.03327.

John Cooper, Emeritus Information Officer, Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, 18 July 2025

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español